The COVID-19 pandemic created, embellished and gave impetus to a range of movements that have at their core a belief in one concept. Namely, that the pandemic itself revealed or confirmed that global conspiracies are in play, as governments and authorities ultimately seek to harm the populace.

Enter “My Place”. One of the many anti-vaccine groups to percolate from the barrage of disinformation during COVID, it was formed by Darren Bergwerf to oppose COVID vaccinations. It began to attract attention after disrupting council meetings earlier this year. Brandishing all the attributes of the freedom movement, My Place urges adherents to form council action groups with the aim of “controlling council decisions”.

Amongst councils targeted this way was Yarra Ranges Council which, in response to abusive and intimidatory behaviour from the public gallery, took council meetings online in April this year, temporarily closing the gallery. Foremost amongst My Place obsessions is the concept of 20 Minute Neighbourhoods or Smart Cities, which conspiracy theorists believe are covert plans to restrict movement, monitor activity, remove freedom of choice and launch an all-seeing digital ID. With textbook conspiracy theory thinking, My Place wrongly assumed the Monbulk Urban Design Framework (UDF) draft plans, accommodated such a nefarious scheme.

Yarra Ranges had openly encouraged community consultation on the UDF, from 16 December 2022. My Place action group members attended the 31 January 2023 council meeting causing enough disruption to temporarily stop proceedings. Council members were yelled at, called a range of names, accused of hidden motives and had their professional integrity questioned. Council then published Statement regarding misinformation on social media on its website, in which it clarified the purpose behind 20 Minute Neighbourhoods and the manner in which technology may be used. This included:

The intent is for people to be able to move about easily and freely without being burdened by excessive travel or costly transport options. It improves movement and access, rather than preventing it.

Sometimes technology can be used to understand where there is congestion on a path or road network or an intersection… [or] when a bin is full or when a drain is blocked, helping to stop litter entering waterways and flooding.

The decision to move council meetings online is permitted under security provisions in the Local Government Act 2020 [see 66 (2)(b)(c)]. Online meetings were available to the public, and at the time, Yarra Ranges mayor Cr. Jim Child stressed he would review the situation in June. In-person council meetings with registration requirements resumed on 11 July. However in a June media release, My Place contended they had been “locked out” of meetings and more so, Council had done this merely due to “perceived” threats to safety. It was a breach of the human rights of residents by Council, and “deeply insulted” by comments that the mayor had made, My Place submitted an application to the Supreme Court. Their orders are laid out below.

And so it came to pass. On 4 July 2023 the matter came before Supreme Court Justice Melissa Richards. The sole plaintiff seeking an interlocutory injunction to prevent Council from adopting the proposed UDF was Darren Dickson, who represented himself and had submitted affidavits from 18 members of the Yarra Ranges community. Dickson has been described on social media as a “pseudo-law guru”, although I cannot attest to the import of this particular honorary. Justice Richards set a trial date for 3 August 2023.

Dickson sought the injunction based on a lack of community engagement, and further:

- An extended 12 month consultation period.

- Council to reopen the public gallery for meetings.

- Clarification on filming from the public gallery.

- Contended Council did not meet Local Government Act 2020 (Vic) requirements.

- Contended Council was in breach of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act (Vic) 2006, namely right to privacy, to freedom of expression and participation in public life.

Mr. Dickson also sought answers to two questions specific to the manner in which he perceived the implementation of 20 Minute Neighbourhoods (20MN). Namely:

- Whether Council’s role includes power to develop three storey accommodation for local areas.

- Whether Council can engage with and adopt United Nations policies.

Whilst not living in the municipality Dickson identifies as a member of the community. He works and socialises there and cares for his mother who is a Yarra Ranges resident. Dickson had attended the disruptive 11 April council meeting that led to temporary closure of the public gallery.

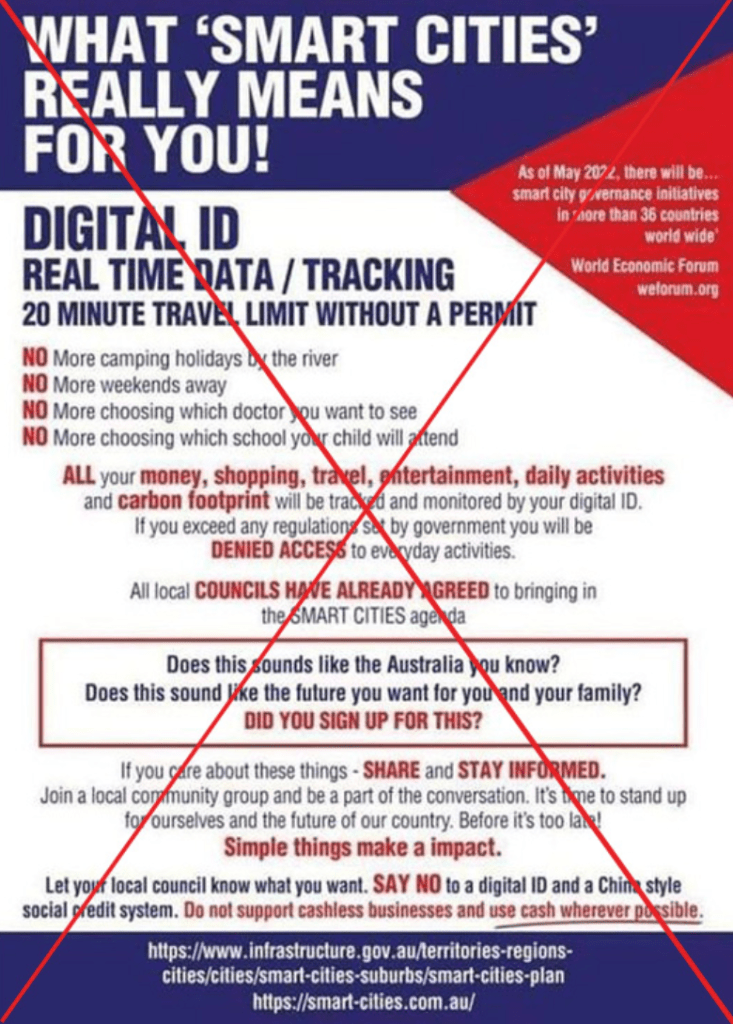

Lilydale resident Martin Dieleman was concerned that the UDF proposed by Council would permit 20 Minute Neighbourhoods and in turn, this would ensure increased surveillance and housing density along with restricted choice and freedom of movement. He started a petition in March this year, promoting the well debunked conspiracy theory view of 20MN and by June had over 2,000 signatures from across Victoria. Absurd claims about smart cities had by then become an increasing feature of social media, resonating with those convinced by the “freedom movement”. Dickson had bought the narrative and learned of growing attention to the Monbulk UDF from Dieleman in April this year.

Smart City disinformation poster [source]

Throughout the consultation period Council had made themselves available to discuss and clarify aspects of the UDF. Specific community engagement programmes organised by Council were provided, along with multiple interactions with individual community members. The draft UDF is discussed in the below video published on 11 February 2023.

Nathan Islip, Manager Design and Place talks about the Monbulk UDF

Edward Gisonda, counsel for Yarra Ranges Council, submitted that being part of the community does not give Darren Dickson standing to seek public law remedies regarding approval of the UDF, conduct of Council meetings and the two questions regarding 20MN. In her judgement of 199 paragraphs over 62 pages, Justice Richards found Darren Dickson did not have standing to pursue legal action. More specifically Dickson did not demonstrate that he had special interest in the UDF, or that if approved by Council, it would have a legal or practical effect on him. His interest is no different to that of any member of the public.

Her Honour wrote [para. 46]:

I accept that he is concerned about aspects of the UDF, although these concerns seem to be based on misunderstandings of the UDF’s content and effect. An intellectual or emotional concern, however strongly held, is not enough to give Mr Dickson standing to obtain public law remedies in relation to the Council’s consideration of the UDF.

Nor could Dickson demonstrate a special interest in how Council held its meetings, and he did not submit that he had difficulty accessing or viewing council meetings when held online. Dickson did submit affidavits for 11 local residents who had privacy concerns about the registration process for attending in-person meetings but Dickson himself was not one of them. Nor had he sought consent to record any council meeting.

Justice Richards wrote [para. 48]:

At its highest, Mr Dickson’s interest is a strongly held belief that the Council should conduct its meetings in a particular way. On its own, that is not enough to establish standing to obtain orders compelling the Council to conduct meetings in that way.

Justice Richards went further and considered if someone with standing would secure the legal remedies that Mr. Dickson sought. This involved examining evidence and testimony presented at trial and viewing Council performance through the lenses of the Local Government Act, the Planning Act, Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 [Vic] (the Charter) and Plan Melbourne 2017-2050: Metropolitan Planning Strategy. There are some interesting aspects to the judgement.

One contention raised by the plaintiff and revisited during questioning was that the council had failed to “meaningfully engage” over the UDF, with particular emphasis on the temporary closure of public meetings. Council is bound by the Charter to ensure the right to engage with public affairs is observed. Yet this doesn’t give an individual the right to dictate terms of their involvement. Council’s community engagement with respect to the UDF, and the involvement of Nathan Islip in attempting to assuage concerns of some residents, covered 10 pages of the ruling.

Mr. Islip’s patience is evident, in that he was clearly repeating answers to the same questions from the same resident/s via email, over the phone, in person and during council meetings. He fielded questions over freedom of movement, privacy and “tracking of movements” in 20MN. At one meeting he was asked if there would be “consequences for travelling outside of our 20MN”. Addressing whether or not Council met community engagement obligations specific to the UDF, Justice Richards ruled overwhelmingly that they did [para. 70 – 125].

Justice Richards rejected six complaints raised by Mr. Dickson highlighting different means by which Council purportedly failed to provide adequate community engagement. Addressing each in turn Her Honour ultimately wrote:

Mr Dickson has not established that the Engagement Plan adopted by the Council for the UDF limited his or anyone else’s Charter right to participate in public affairs. The right does not enable any member of the public, regardless of their interest in the UDF, to dictate the terms of the Council’s engagement with the community about the UDF, or to demand immediate answers to questions about matters not contained in the UDF.

As had been clear from the My Place media release and questions raised by David Dickson during the hearing, the fact that online council meetings had been held from 26 April to 27 June 2023 was considered a breach of the Local Government Act by the plaintiff, because these meetings were not “open to the public”. However the Local Government Act is clear in this regard. Justice Richards wrote:

Mr Dickson’s complaint that the Council had closed its meetings to the public between 26 April and 27 June 2023 was misconceived. […] A council meeting is ‘open to the public’, as that term is defined in s 66(6) of the Local Government Act, if the meeting is broadcast live on the internet site of the council.

Let’s recall, dear reader, that meetings moved online in response to repeated abuse and aggressive behaviour from the public gallery. Justice Richards recounts in detail, evidence from witnesses concerning the intimidation [para. 157 – 169]. During the trial David Dickson cross examined witnesses, seemingly intent on dismissing what they had already reported as intimidating or threatening experiences. Nathan Islip had given evidence that “threatening comments” were made at the 31 January council meeting, to which police were called. Dickson asked Mr. Islip if he knew what “the definition of a threat is”. Here, Dickson is focusing on the threat of harm, seemingly unaware that intimidation in pursuit of coercion is also a threat.

Notably, Justice Richards observed [para. 165 (a)]:

There was a group of people among the large public gallery who were intent on disrupting the meeting, and who did so. They interjected frequently and loudly and did not recognise the authority of the Mayor as Chair of the meeting. Their behaviour was contrary to r 73.3 of the Governance Rules, in that they did not extend due courtesy and respect to the Council and its processes, and they did not take direction from the Chair.

With respect to filming council meetings, attendees wanting to do so must seek consent of the Chair. Pre-registration with photo ID for those who want to attend in-person meetings has not been shown by Mr. Dickson to be unlawful. It is permitted under the Local Government Act and the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004. Evidence was given by Andrew Hilson, Yarra Ranges Director of Corporate Services, that information collected is in accordance with the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014. Justice Richards ruled that given prior disruption to council meetings, registration is proportionate and not an unlawful interference with the right to privacy.

This brings us to the two additional questions Dickson wanted answered regarding three storey accomodation and the adoption of UN policies. In fact they arise from a misunderstanding of the origin and scope of the UDF. There is no evidence that Council is seeking to develop three storey accomodation for local areas. Nor is there evidence that the UDF heralds adoption of UN policies. Rather, the UDF does not actually refer to 20 Minute Neighbourhoods. In the event that it did, it would in fact be Victorian Government policy and an existing part of the Yarra Ranges Planning Scheme.

More importantly however, is that David Dickson does not have standing to seek answers to these questions. Again, his interest is no different to any other member of public. Justice Richards wrote:

In short, the additional questions should not be answered because they do not relate to any legal controversy between the Council and Mr Dickson, or the Council and anyone else identified in the evidence.

Ultimately, there were no democratic principles or legislation breached by Yarra Ranges Council during UDF consultation, or as a result of temporarily changing meetings to online. Online meetings are not only available to the public but are the preferred option for many. Yarra Ranges Council posted a response to the ruling on their website here.

Darren Dickson was ordered to pay Council’s costs. If in disagreement, he has until 1 September 2023 to submit his reasons as to why a different order should be made.

One cannot ignore that as sovereign citizens, My Place supporters reject the notion that Australian courts, laws and institutions hold any valid power. Exactly how this ruling will be accepted remains to be seen. Might it be rejected outright, or woven into the complex tapestry of the parallel society My Place founder Darren Bergwerf aims to create? Sov Cits are skilled at rationalising dissonant outcomes as victory. It may be that taking a Council to the Supreme Court can be accepted as a win. Of sorts.

Either way, the theme of corrupt public authorities was also evident in the many unsuccessful cases involving anti-vaccination groups and vaccine mandate opponents, recently making their way to court. They too had “woken up” to a new reality. Many were exploited or left in debt. Established anti-vaccine pressure groups had retooled for COVID. They continue to promote themselves, and financially profit to this day.

Not one has been, or will be, denied an opportunity to access the court system and bring their evidence, no matter how disjointed and deceptive, before a judge. Ultimately, this particular case has, like the others, reinforced the strong democracy Australia has.

Evidence for a corrupt global cartel however, remains elusive.

Thanks Paul.

I’ll gird my loins for a read.

Tim

LikeLike