Critical overdose events at three Australian dance parties in January this year, have led to more calls for Pill Testing (PT) to be introduced as part of our nation’s effective Harm Minimisation drug policy. Harm Minimisation consists of three prongs: Demand Reduction, Supply Reduction and Harm Reduction.

Strong evidence

Pill testing is an evidence-based, harm reduction initiative backed in peer reviewed literature. It reduces drug harms and protects the health of those who access the service. Whilst Australian drug markets are uniquely sourced and specifically affect Australians, Harm Reduction Australia cites Harm Reduction International, in answering the question, What is harm reduction?

Harm reduction refers to policies, programmes and practices that aim to minimise negative health, social and legal impacts associated with drug use, drug policies and drug laws. Harm reduction is grounded in justice and human rights. It focuses on positive change and on working with people without judgement, coercion, discrimination, or requiring that they stop using drugs as a precondition of support.

PT has been demonstrated via live trials at Canberra’s Groovin The Moo festival in 2018 and 2019, to be effective in positively changing behaviour related to drug use. The trials were conducted by Pill Testing Australia, and resulting evidence greatly contributed to the fixed-site testing facility CanTEST, an ongoing trial in Canberra, introduced in July 2022. Indicating the controversy of PT, days before a third dance festival trial was scheduled to begin in 2022, Pill Testing Australia had public liability insurance withdrawn, without explanation.

A 2019 election study found two thirds of Australians support PT at music festivals. Examining deaths, PT initiatives, the success of harm reduction and drug user responses, Andrew Groves wrote in The Harm Reduction Journal in 2018:

Using a theoretical frame of pragmatism and drawing from national and international research evidence, this paper recommends the integration of pill testing into Australia’s harm minimisation strategy.

Australia’s Alcohol and Drug Foundation have published an excellent summary of the evidence supporting PT, and provide data on its successful international uptake. They also point out that public health experts have demonstrated support for PT. These include:

- Public Health Association Australia

- Australian Medical Association

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia

- Royal Australian College of Physicians

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)

Queensland

In February 2023, directly citing the success in Canberra, the QLD Palaszczuk government announced plans to develop Drug Checking at fixed and mobile sites. This very shortly followed the state’s plans to reduce penalties for illicit drug possession, including heroin, ice and cocaine. More so, use of the term “drug-checking” is more realistic, inclusive and in line with international practice, as summed up in this opening paragraph from the QLD Network of Alcohol and other Drug Agencies (QNADA):

Drug checking – also sometimes referred to as ‘pill testing’ – involves members of the public voluntarily providing samples of suspected illicit substances they are intending to consume (e.g. tablets, capsules, powders, tabs/blotter paper etc) for chemical analysis.

Test results are provided back to the individual by health professionals as part of a personalised health and harm reduction intervention. The purpose of the intervention is to increase the person’s awareness of the risks associated with the substance with the aim of effecting behaviour changes that result in fewer harms or incidences of drug-related death.

In September last year the QLD government sought private providers to offer plans for two fixed drug-checking sites and mobile services. Of course, great strides like this rarely escape unhelpful politicisation. It was impossible to miss that when announced, the decision was called “soft on drugs” by QLD opposition health spokeswoman, and registered nurse, Ros Bates. It’s been a long time since I’ve heard that phrase used seriously.

Victoria

It is Victoria, to where we must turn our attention to partly examine the recent overdose events. RACGP reported eight people, most in their 20s were intubated and placed in induced comas after MDMA overdose at the Hardmission dance party in early January. Jollyon Attwooll reported:

Chair of RACGP Specific Interests Addiction Medicine Dr Hester Wilson described the introduction of festival pill testing as ‘a no-brainer’.

‘[Pill testing] actually does change people’s behaviour, and therefore it makes it safer,’ she told newsGP. Dr Wilson said that pill testing is ‘not a silver bullet’ but should be used as part of a range of measures to address drug use.

Following the Hardmission OD events, two women were taken to hospital on January 12 after suspected drug use at Juicy Fest. Current Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan initially stated she had no plans to introduce PT. Not long after, Allan advised that she would seek more information from the health department. The Premier sensibly observed:

I think it’s important to examine the evidence and advice and consider that in the policy setting that we have across all of our alcohol and drug policy measures, which is taking a harm minimisation approach, looking at the safety of people going to events.

The ACT

The evaluation document of the 2019 ACT Pill Testing trial is a lengthy read, with confirmation of Dr. Hester Wilson’s words coming through in data and discussion. I won’t copy/paste quotes from patrons who attended the PT facility, but I do recommend skimming through to appreciate that PT, like other harm reduction initiatives, changes drug users behaviour for the better. I did appreciate the graphs on self-reported knowledge of harm reduction before and after having a drug tested. Likewise, when it came to choice of information source, positive changes are evident.

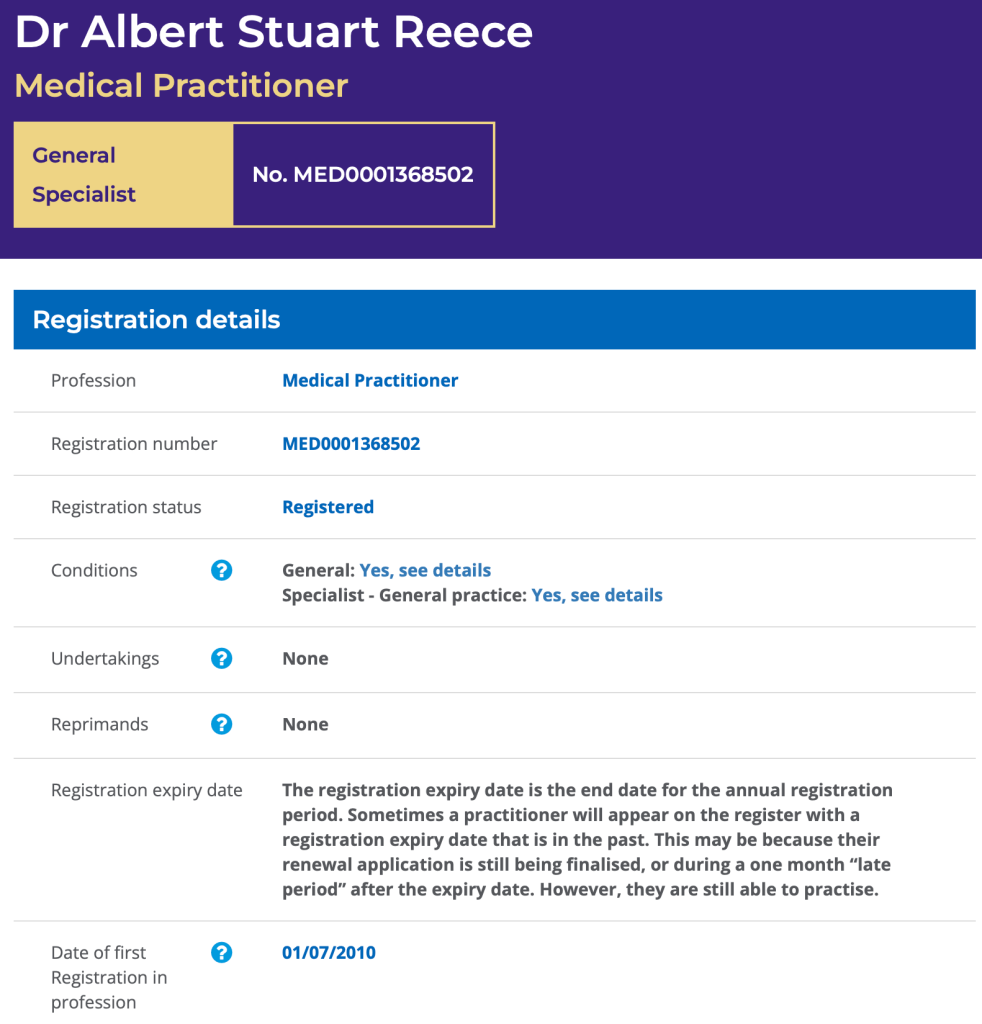

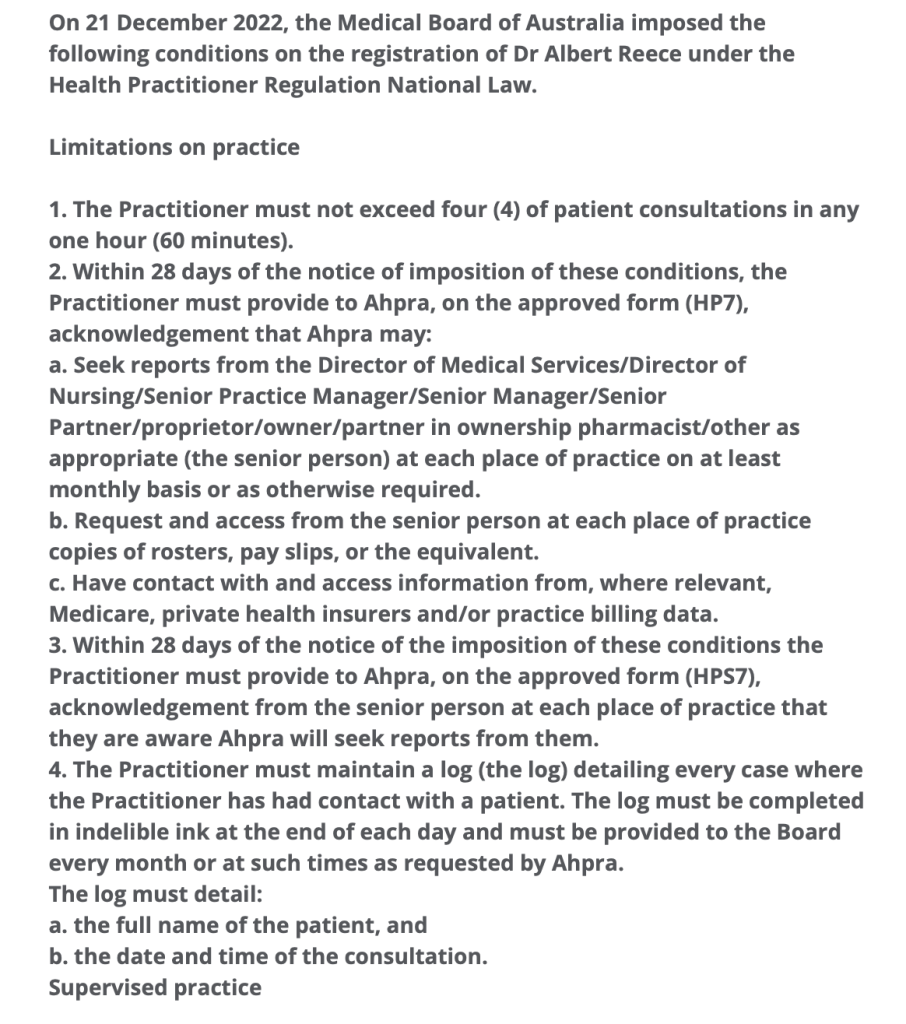

Detailed explanation of the slides below can be found at section/s 6.1 (fig. 1), 6.4.1. (fig. 3) and 6.4.5. (fig.4).

Sydney

At the end of January a challenging scenario unfolded at Sydney’s HTID festival. Having taken what he thought was MDMA, an attendee fell unwell. Ultimately he responded to naloxone, a drug that reverses the effect of opioids. He had taken a tablet cut with nitazene, which is a synthetic opioid reported as “stronger than” fentanyl or heroin. Health workers and members of drug safety volunteers DanceWize, worked to advise the crowd. No doubt they saved lives. It turned out others from around Sydney had been hospitalised that weekend. One pill analysed, contained nitazene and no MDMA. Guardian reported:

Chris Gough, chief executive of the nation’s only pill testing venue in Canberra, said the detection of nitazenes in pills sold as MDMA showed the need for similar services in other states.

“In this case, where a nitazene has been sold as MDMA and therefore people are completely unprepared and potentially opioid naive, the risk of overdose is extreme,” said Gough, who is the executive director of the Canberra Alliance for Harm Minimisation and Advocacy.

“As we have now seen nitazenes in several jurisdictions in Australia it is time to act swiftly to provide drug-checking services throughout Australia so that we can respond to these drug trends as they emerge and thereby save lives and inform the community.”

Canberra

Saving lives is far more about probability than possibility. Indeed that’s been the case with MDMA overdose, MDMA pills cut with N-ethylpentalone or other adulterants. Early last year the Canberra walk-in site CanTEST discovered a pill cut with metonitazene; a synthetic opioid with a potency up to 200 times that of morphine. The owner chose to dispose of the drug on site. In January this year, ANU chemists made an Australia-first discovery of three new recreational drugs. All came from preparations sold as something else. CanTEST staff were able to discern the drugs were not what they were supposed to be, but tests were inconclusive. They were however, able to warn the community. One substance thought to be a derivative of Ritalin was in fact a new variant of cathinone, commonly known as “bath-salts”.

ACT Health have also developed a comprehensive document for festival planners. The Festivals Pill Testing Policy, examines PT options as a service available for festival attendees and how it relates to harm minimisation. Advice on general and specific health and safety measures, the importance of peer support, relaxation areas, emergency services and how PT works with providers and the event itself, is only part of the clear information presented.

Coronial support

A number of fatalities, and the fact that PT promotes positive decision making led to multiple calls to introduce the practice as a policy initiative. Over the last six years, four state coroners have spoken out. A 2020 inquest into five deaths from July 2016 to January 2017, led Victorian coroner Pares Spanos to urge the Victorian government to “urgently” introduce drug checking and a system to warn the community about dangerous substances sold as MDMA. The males aged from 17 to 32 died in a variety of tragic ways after taking what they believed was a modest dose of MDMA. Autopsy revealed the substances 25C-NBOMe and 4-Fluoroamphetamine in their systems. The cluster was discovered after 20 hospitalisations stemming from the Chapel Street nightclub district in January 2017. Victoria Police knew of the dangerous drug’s presence and later defended their decision to not warn the community.

In September last year, Victorian coroner John Cain also called on the government to introduce PT after the death of a man from an MDMA overdose in March 2022. The man had been observed taking a Blue Punisher, a pill with dangerously high levels of MDMA. He was admitted to the Royal Melbourne with brain swelling and multi-organ failure and died four days later. In his findings Cain wrote:

It is impossible to know whether, had a drug checking service existed, [the man] would have submitted a sample of an MDMA pill for testing before taking it at Karnival […] Notwithstanding this, a drug-checking service would have at least created the opportunity for him to do so, and for him to receive tailored harm reduction information from the drug-checking facility.

It is likewise impossible to know whether, had [the man] been provided information of this type, he would have changed his drug consumption behaviour; but likewise, in the absence of a drug checking service, this was not a possible outcome.

Politics

NSW and Victoria have established histories of resisting PT. After the death of a 26 year old at a Sydney music festival in February 2023, Dominic Perrottet mused about his government’s inquiry into methamphetamine and, rejecting any notion of PT offered a most unhelpful contribution:

But my clear message to people right across NSW [is] stay safe, and don’t take drugs and you will be safe.

Associate Professor David Caldicott, one of the driving minds behind CanTEST, suggested Perrottet had engaged in “magical thinking”. In Victoria we have the legacy of Dan Andrews who, citing the demonstrably false [HRJ] claim that PT encouraged pill taking (a belief favoured by Craig Kelly), insisted that under his leadership PT would never be introduced. The state opposition has been steadily opposed to harm reduction measures for conservative political reasons. Ignoring evidence, consecutive opposition leaders have opposed Safe Injecting Facilities and PT alike. I do acknowledge however, that the Victorian opposition has lobbied the state government for more effective emergency drug alert systems.

Recent research

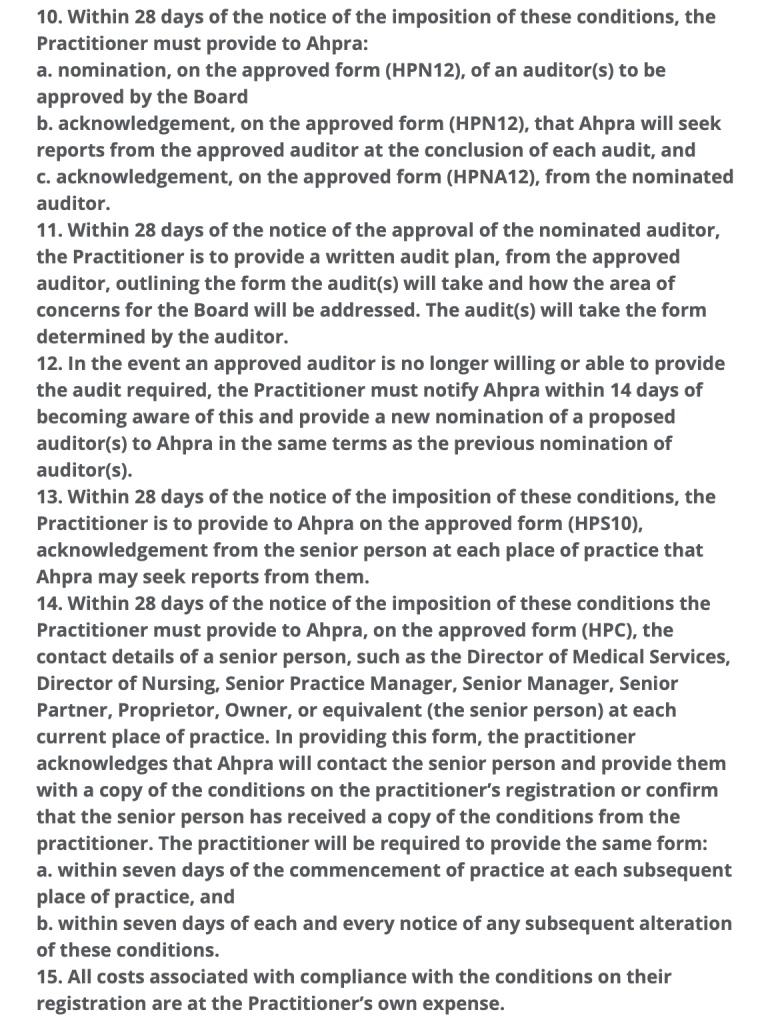

A recent paper Drug-related deaths at Australian music festivals, was published last month in the International Journal of Drug Policy. Examination of the National Coronial Information System (NCIS) yielded the following results about fatalities at music festivals between 2000 and 2019:

There were 64 deaths, of which most involved males (73.4%) aged in their mid-20s (range 15-50 years). Drug toxicity was the most common primary cause of death (46.9%) followed by external injuries (37.5%). The drug most commonly detected or reported as being used was MDMA (65.6%), followed by alcohol (46.9%) and cannabis (17.2%), with most cases reporting the use of two or more drugs (including alcohol) and 36% reporting a history of drug misuse in the coroner’s findings. Most deaths were unintentional, with less than a fifth of cases (17.2%) involving intentional self-harm. Clinical intervention was involved in 64.1% of cases and most festivals occurred in inner city locations (59.4%).

There are complex factors identified in the paper, such as inner city events and multi-day events being more likely to be the site of a fatality. This may reflect policing strategies and the need for harm reduction strategies, respectively. Alcohol is known to be a compounding factor and its use is clearly identified as the second most prevalent substance (see bar graph below). Males are more likely to drink and use MDMA and this is reflected in them making up just under three quarters of deaths. Of 2000 festival goers surveyed, 52% were male. Poor decision making associated with alcohol intake is always a potential factor with illicit drug use.

Harm reduction flexibility

What I took away from this paper was the recommendation that a range of harm reduction measures would each have something to offer in solving this persistent, multifactorial problem. More so, understanding data yielded by such research is vital to establishing the correct harm reduction approach for the Australian population in these instances. In conclusion, the authors write:

Harm reduction strategies such as roving first aid volunteers, mobile medical care, spaces to rest, hydration stations, and drug checking services, may best address some of the risks associated with illicit drug use at festivals, in addition to increased consumer education and awareness. It is important to understand the factors involved in these incidents in order to inform policies around harm reduction and law enforcement at music festivals in future to prevent further deaths.

Just as is the case with injecting facilities, substance checking is a successful, global health policy dynamic. Like all aspects of harm reduction the evidence supporting it is strong, persisting through variations specific to where it is a reality. In Canada, Toronto ran a comprehensive trial from 2019 to 2023. Switzerland has had drug checking available since the 1990’s. Now in a number of cities, the past decade saw a 250% increase in samples tested there. The UK has drug checking services, as does New Zealand.

Despite certain dynamics in NSW and Victoria leaving state governments out of touch with most Australians, there are cabinet ministers and cross-bench teams respectively, raising awareness and pushing for change in each state. When we look at arguments for and against PT, it appears arguments against, lack realistic substance. Indeed these documents recognise the importance of harm minimisation and its place in the National Drug Strategy. The most comprehensive argument “against” is criticism of the limitations of on-site drug checking, compared to laboratory testing. This is well understood and has been directly addressed by Dr. Monica Barratt. Of course the inevitable case that flexible harm reduction measures encourage or create the illusion of safety around illicit drugs is always mentioned. The evidence simply does not support this.

Drug Free Australia

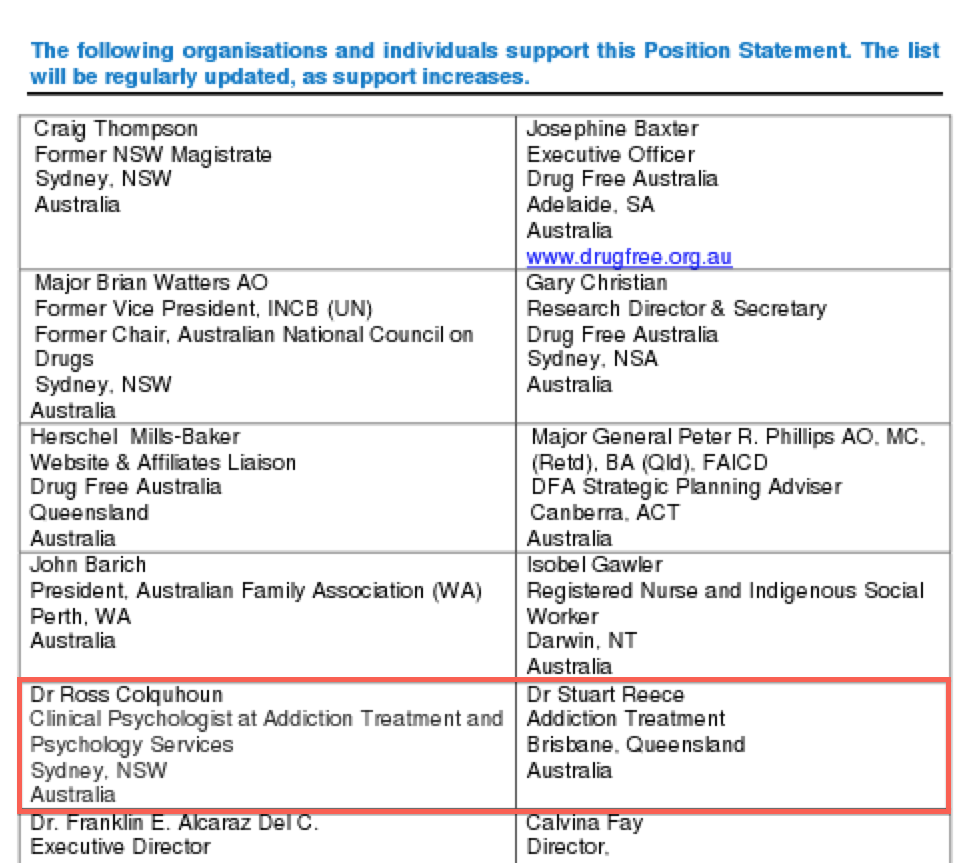

This brings us to the anti-drug lobby. Certain groups contend that law enforcement and zero tolerance are superior in managing drug related harms. Stridently anti Harm Minimisation, they promote the ideology of a drug free world, consistently undermining evidence. In fact my own interest in the anti-vaccination lobby, began in 2009 and I was struck by similarities between their tactics, and those of the more lethal anti-drug lobby, I was long familiar with.

One group, Drug Free Australia (DFA), operate similarly to The Australian Vaccination-risks Network (AVN). DFA aggressively lobby government and an unsuspecting public, frequently using alarming irrelevant information. They attack the media, use meaningless or decontextualised data to dispute published evidence or argue that acknowledging a need for more research, reveals lack of any research. DFA dismiss harm reduction techniques by highlighting the ongoing presence of harm (eg; MDMA has caused deaths, thus no rationale for PT exists) or blame harm reduction for drug user risk-taking, and the familiar contention that PT “green lights” the taking of MDMA.

Such contentions stem from ignoring that high risk behaviour via illicit drug use continues all day, every day in Australia. Harm reduction aims to reduce the harms associated with this behaviour. It provides education, promotes safe choices, saves our health-system money, and yes, saves lives. One way DFA contend PT actually kills, is by misrepresenting the PT card system. A drug found to contain what the owner expected is “white-carded”; as is say, an MDMA pill free of any pollutant. Yet, MDMA causes most overdoses say DFA, so a white-card result must be potentially lethal. Well, no. The drug is what the person expected. Not double or five times the amount. So the patron may take the drug they bought and, remembering the slide show above, will henceforth access reputable information on harm reduction.

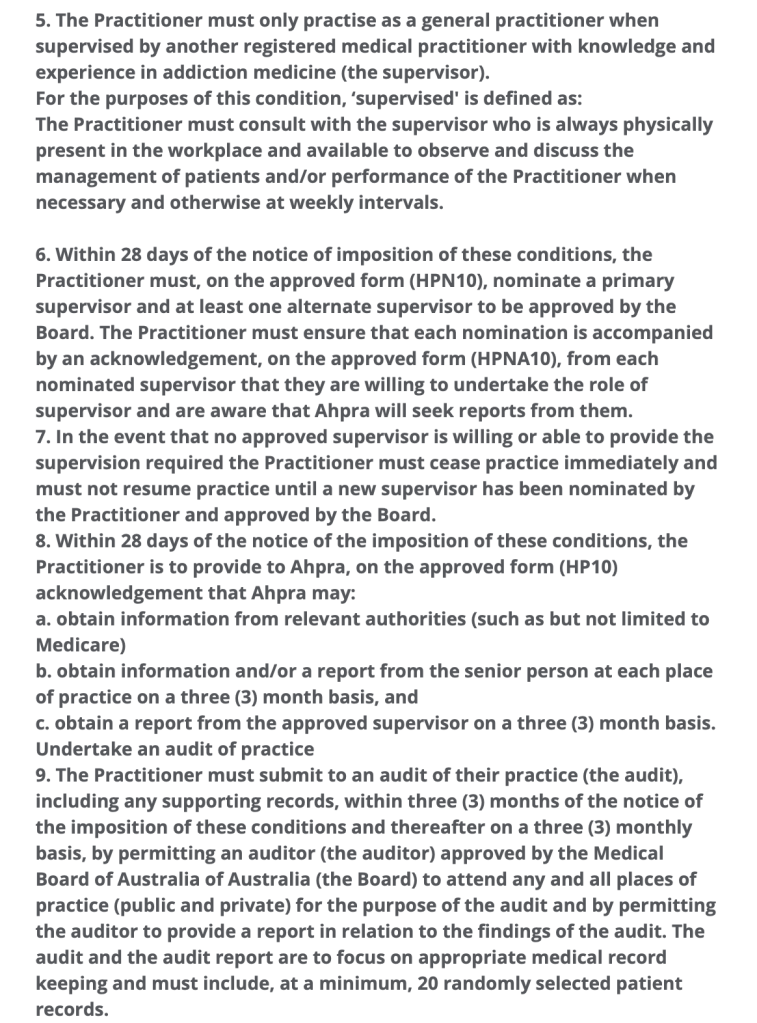

Those slides are from the ACT Pill Testing Trial 2019. DFA attack those findings in a deceptive piece, arguing the opposite to accepted findings. On page 7, they selectively quote from evaluators who discuss that someone who discovers that the drug is what they thought, “…are likely to take as much or more” (p.33). And that “…concordance between expectation and identification is associated with stable or increased intention to take a substance” (p.34). DFA use this to extrapolate to the conclusion that PT will lead to more use and thus, more death. This requires logical fallacies: Decontextualisation and cherry picking of data. Reading the full sentences and paragraphs in which those terms appear leaves the reader with a positive, not negative view of the evaluation. See pp. 33-34, and consider Table 5 from p. 32, below:

When read in context we see that patrons intent to use drugs did not dramatically change, but their intent to engage in harm reduction behaviour notably increased. Eg, also on p.33 (bold mine); Many interviewees reported that the quantity of drugs that they intended to use did not change after testing, as the drug was identified to be what they expected. And, Many interview patrons indicated that their intention to use did not change, but their intention to engage in harm reduction behaviours did increase. Also, this and other evaluations have found non-concordance between patrons’ expectation of what a substance is and what a substance is identified to be, commonly leads to reduced intention to take that substance.

So, the comment pulled from p. 33 by DFA, omits crucial clarification from the evaluation. Some was printed on the same page, just two paragraphs above. For example:

Interview data suggests that this group were looking for confirmation of the contents of the presented drug, and information about how to reduce potential harms. Many interview patrons indicated that their intention to use did not change, but their intention to engage in harm reduction behaviours increased.

Prior research also indicates concordance is associated with an increased likelihood of taking the drug, and non-concordance with a decreased likelihood (Valente: 2019, and Measham: 2018). More so, the evaluators stress that modification of drug consumption can’t be measured alone. Contextual factors, such as type of festival influencing available drugs, need to be considered during interpretation of results and future study design.

Finally, the insistence by DFA that MDMA, not impurities, lead to most fatal overdoses is fashioned only to discredit PT. Still, five deaths in the six months leading up to January 2017 and investigated by Coroner Pares Spanos involved 25C-NBOMe and 4-Fluoroamphetamine. Recent discovery of potent opioids nitazene and metonitazene raise further concern. N-ethylpentalone is regularly found in so-called MDMA pills. But why get hung up on MDMA? Drug checking can check any drugs and CanTEST discovered three unknown substances, later confirmed at ANU. This is how a new type of cathinone (bath salt) was found. Supposed ketamine was actually a new type of benzylpiperazine (BZP) stimulant. The third find was propylphenidine.

Conclusion

Pill testing or drug checking is a harm reduction measure supported by consistent evidence in peer reviewed literature. Globally, where introduced, it has demonstrated success and improved understanding of behaviour. It is supported by most Australians, where valuable data has been gathered from on-site testing at music festivals, and the fixed site CanTEST, in Canberra.

This has expanded the nation’s understanding of drug user insight into, and uptake of harm reduction dynamics. QLD is the most recent state to confirm permanent drug testing. Arguments against the initiative are morally subjective and/or deceptive, leading to their swift deconstruction.

Drug checking saves lives and is supported by public health experts across Australia. As a dynamic, expanding, harm reduction initiative, it should be introduced nation-wide into Australia’s harm minimisation strategy.

♠︎ ♠︎ ♠︎ ♠︎

Originally published as Pill Testing: The harm reduction initiative supported by strong evidence